Design and Operation of a Crowd-Run Distributed Outdoor Game

Table of Contents

| App | http://hideandseek.ninja/stockholm.html |

|---|

NB: This project is down for maintenance.

The Pre-Game⌗

In May 2015, Aaron Luo, Anna Robbins, Claudio Paganini, and I sat down and designed a model for a new type of event: a free, outdoor, massive game of hide-and-seek. We would attract attention through a Facebook group, and have participants read rules and register on a website (http://hideandseek.ninja/) (which I would build and maintain) during the game.

What was the incentive for such an unusual event?

Legal Considerations⌗

We were inspired by stories of people playing Hide and Seek in an Ikea. This is both a) very Swedish, and b) very illegal. Private property and unregistered events don’t mix well. So our event had to be outdoors, public, unlisted, and legal.

We realized that concerns of legality rarely had to do with attendance – they had more to do with density. Enough people in the same place would clog traffic, call attention, get us shut down, etc. But thousands of people could still play - as long as they were not all in the same place.

But, most importantly, it had to be disorganized. The idea of standing in a city square with a megaphone trying to shout instructions to hundreds of people was not an appealing one.

Thus was born the distributed game.

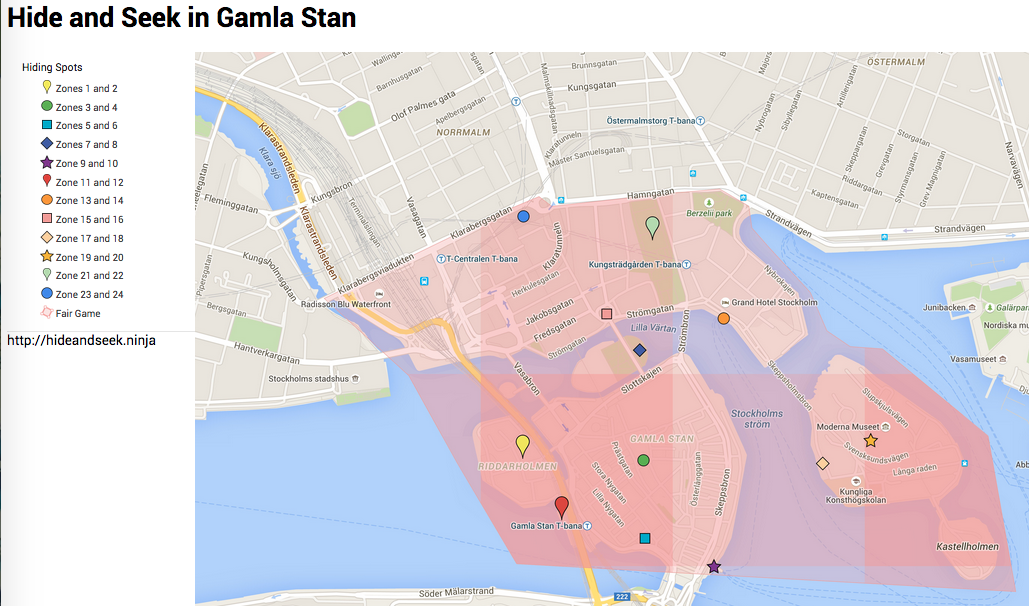

Imagine twenty or so little games of Hide-and-Seek going on all around the city. There are under 40 people per game, and each game is self-contained, each with its own meeting point and region. Stray too far from one zone, and you begin to encounter players from another. The game could grow organically as more and more people were invited, and it wouldn’t affect gameplay at all – as long as we distributed the game over a large enough area.

But how would the game work?

Math and Scoring⌗

Hide and Seek in Gamla Stan operated on a unique scoring system designed by Claudio Paganini.

Each player starts with 100 points. They then share these 100 points with those seekers find them. Thus, if I am found three times, each seeker recieves 25 points, and I, the hider, keep 25 points of my points. When the roles are reversed, I do my best to find many hiders and recoup my losses.

(How do you prove you found me? We’ll get there in a moment.)

The benefit of this system is that suddenly the game requires strategy. In a short game period, the seeker can only find so many hiders. The share system means that seekers are rewarded not only for quantity of finds, but quality – those hiders who are more difficult to find are found less, and each share of their points is worth more. One really good find can be worth as many as 50 points. A bad find could easily be worth 5.

How would you prove you found someone?

Proof of Find⌗

From the beginning, we wanted people to be able to play without supervision or oversight. Thus, rather than verify finds by hand (impossible) or rely on an honor system, we chose to verify finds mathematically, with a small bit of information.

Each hider was, at registration, given a secret code (mine was B030) to share with those seekers who found them. The seekers would then write down the code in a notepad, on their phone, whatever. After the game, they could go to the website, enter the code, and verify their find.

As the players logged their finds, we began to generate a graph of finds across town.

How were the codes generated?

Design of the Secret Code⌗

Anna Robbins and I struggled with the concept of a ‘secret code’ for a few days. A short text string was easier than something more verifiable, like a QR code, but language barriers, spelling errors, and handwriting meant that strings, words, phrases, were untenable. We wanted it to be short and sweet, something easy to write and easy to type in afterwards.

Additionally, the codes had to be salted: that is, it ought to be difficult to randomly guess a string and have it be an extant secret code.

$$\underbrace{\texttt{B}}_{\texttt{email_string[0]}} \overbrace{\texttt{030}}^{\texttt{dec2hex}(id)}$$

The first character is an alphanumeric character, the first in their email. The next three characters are the truncated hexadecimal representation of their identification number ($id) in the database. (The $id represents if they were first, second, etc. to sign up for the game.)

The first bit was known to the user; the second was not. The second bit was easy to figure out, if you knew hex; the first was not. It doesn’t stand up to real cryptographic analysis, of course, but it did the trick – we didn’t detect any cheating.

An additional failsafe against cheating was that anybody sharing codes with their friends was effectively diminishing the value of the code. A 25pt find, split an additional way, becomes a 20pt find.

How did we invite people?

Social Engineering⌗

Once the game was designed, the rest was simple. We started a Facebook event and invited every student we knew. I personally asked a few social mavens to invite everyone they knew.

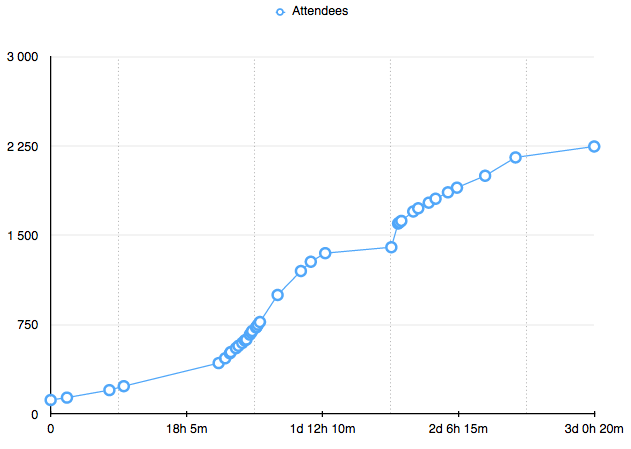

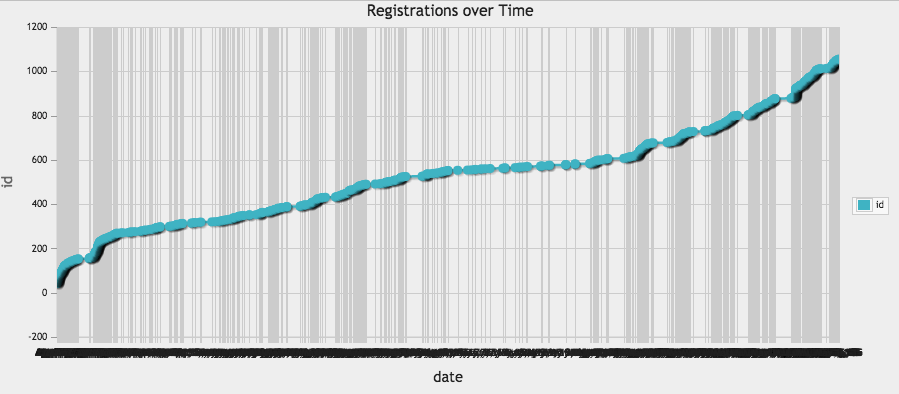

After the first few days, Facebook’s attendance measurement began to lose digits of accuracy. Thus, I only have rate-of-attendance data for the first thousand attendees or so. We eventually reached just over 6k invited / 3.5k attending on Facebook, with just over 1k of those people actually registering to play on http://hideandseek.ninja.

Those Attending on Facebook, vs…

…those Officially Registered on the Website.

The registration system collected the player’s first and last name, email, and hometown. Upon submission of the registration form, each player recieved a customized email containing more detailed gameplay instructions, their secret code, their team (whether they were to hide first or seek first), and their Zone – initially, merely a random number between 1 and 24. (24 is a very divisible number.)

How did we assign zones?

Zones⌗

Once we reached ~800 registered, we began to divide up Gamla Stan and the surrounding neighborhood into 12 zones, and demarcate a region of fair play.

We picked (hopefully) good meeting points (public squares, parks, places far from traffic and palaces) and emailed instructions on a per-zone basis, indicating where to meet, when to begin playing, etc.

Players needed to bring a pen and pad, to write down the secret codes they found. They also needed a watch or something similar to keep an eye on the time – each team had 15 minutes to hide, and 30 minutes in which to stay hidden while the other team sought. Then, after another 15 minutes, they would switch. The game wouldn’t work if people didn’t know where to go when.

Additionally, the players needed another key ingredient…

Socks⌗

The game was called, colloquially, Hide and Sock. Players had to know who was playing and who was just a bystander. We instructed players to wear a sock on their hand, so that they could be found. So they had to bring a sock.

The Game⌗

On the day of the event, I got my sock, pen, paper, watch, secret code, zone, etc – everything I needed – and went to my assigned location, where I found – a dozen or so people hanging around, waiting to meet their zone. It turned out not all of our players were college students – plenty of families, tourists, elderly, etc. We synced knowledge about gameplay and schedules, discussed how we found out about the event, and then - suddenly - it was time to hide.

I hid quite badly, because I wanted to see how many people were actually playing. I was found just over 40 times in 30 minutes, which I think is quite impressive - close to 1000 people were actually playing that day, and I personally shook the hand of just over 1/25 of them.

The game went fast - I regret how tight we made the schedule, and how long we made the hiding period. Too many people were too good at hiding, and were never found.

The Aftergame⌗

As per instructions, we all met in Kungstradgarden for a group photo, where I met many of the players and got feedback on how the event went. We also used Aaron’s selfie stick to take a group photo. (I’m in the center, behind the photographer.)

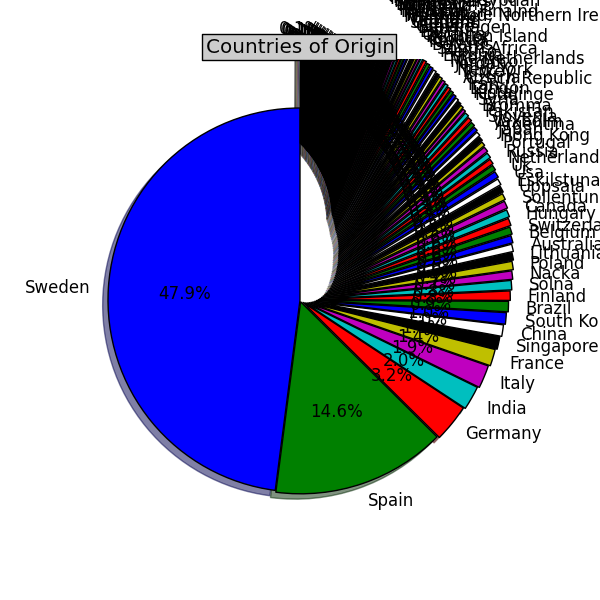

Countries of Origin⌗

When a player registered, we collected their first and last name, email, and hometown (just for fun data analysis). We ended up with 1141 registered players, hailing from 127 regions (countries, large cities, neighborhoods). It’s difficult to graph, but the top three countries were Sweden, Germany, India, Italy, France, Singapore, China, and then over one hundred more with shares under 1%.

Finds⌗

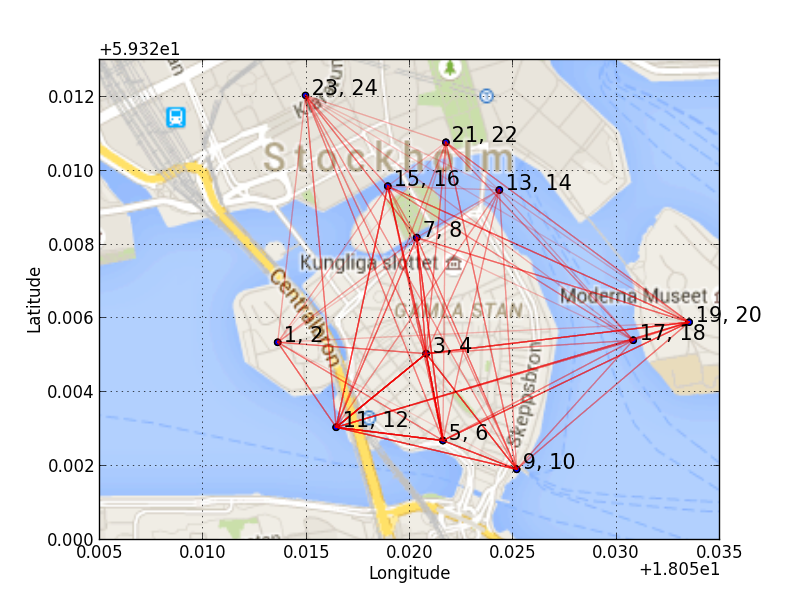

We expected players from each group to mostly end up finding players from their own group. Instead, most people in most zones had the bright idea of spreading as far from their home base as they could. As a result, there was far more cross-pollination than expected. With 1105 registered finds from 139 participating players, 1026 of those finds (92.8%) were of players from other zones. Some zones contained no same-zone finds. The groups quickly disseminated and play roamed free across the city – as intended.

Finds between Zones. Each find is a very light red line. The more inter-zone finds, the darker the red line becomes. Point location is approximate ;)

Altogether, the game was a rousing success, with some players scoring as high as 481 points (found 13 people, was found once).

What Did We Learn?⌗

People are Reliable⌗

The groups were surprisingly self-organizing, and the players were polite, honest, and fun. I met a ton of people, and I think everyone had a great time. (It helped that the weather was great.)

People are Unreliable⌗

On Facebook, anyway. We had 6k invited, 3.5k attending, 1k registered, and just over 150 estimated participants. Under 100 showed up for the final photo.

Knowing this now, we could have made the map a lot denser - I heard reports that some zones were so sparsely populated that finding anybody at all was a challenge.

¯\_(ツ)_/¯